How I published more than entire labs

Without any funding or affiliation with an institution I have been able to publish more than labs with over a dozen researchers and seven figures in funding. And it wasn’t hard. It wasn’t hard because there are large labs out there which haven’t published a single thing in the last year. No papers, no software, nothing.

How is this possible? I’ve had the displeasure of working in some very unproductive labs so I have some insight into the gross inefficiencies of academic research, and these are only more glaring now that I am away from academia performing independent research.

In contrast, now that my office is my apartment I can code for 24 hours straight if needed without any worry of interruptions or a PI asking me where I am.

In contrast, now that my office is my apartment I can code for 24 hours straight if needed without any worry of interruptions or a PI asking me where I am.

Choice of Project

Even the best scientist in the world would be unproductive if he/she worked on an impossible project. Too often projects are chosen solely by the PI, who happens to be the only person in the lab who hasn’t performed research in decades. And these projects are chosen simply because they are seen as “important”, “sexy”, or needed for grant X. They often have no clear end goal: PI: "I want to know what the role of protein X is in process Y." Lab: "Do we have any reason to believe protein X is involved in process Y?" PI: "No, but we study protein X and if we show it’s important in process Y it will be HUGE!" Lab: "Okay, how are we going to do this?"" PI: "I don’t know, aren’t you a scientist? Figure something out." ... PI: "I just read these two Nature publications and I think they are connected." Lab: "Umm, that’s a stretch, but okay, what do you want us to do now?" PI: "I don’t know, get to the bottom of this, if I’m right it’s going to be BIGLY." As a quick contrast, projects I’ve undertaken since leaving UVA have had clear end goals in mind. I wanted to make a better TCGA survival tool than cBioPortal. I didn’t know anything about making a data portal, but there is a lot of information out there about making databases so I was confident that I’d be able to figure it out. Similarly, when I started working on the GRIMMER test my backup plan was always to just create large tables of values. Luckily I discovered a statistical phenomenon which made the test more powerful than I could have imagined, but the point is I was always going to end up with something at the end. Sure you can say that most projects result in a large number of experiments and data. But more often than not these experiments produced negative results and were never published, which effectively makes them nonexistent to the rest of the world.Meetings on meetings on meetings

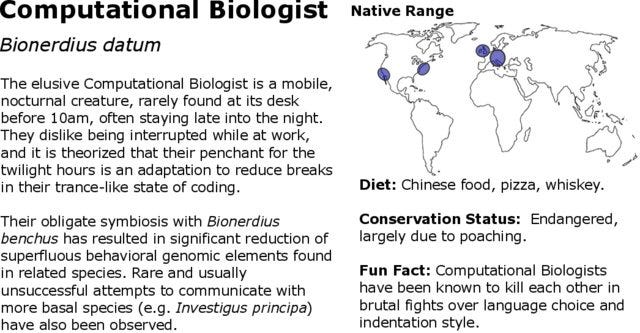

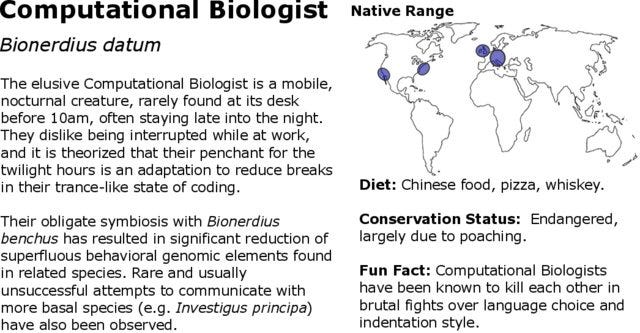

In academia you will have meetings about having meetings. I once had a three hour meeting starting at 9 AM, this was immediately followed by another hour meeting in the same room, and then I got some lunch. Upon finally getting to my office my PI walked in and asked me what progress I had made so far that day. This is an extreme example but it must be emphasized how much time is wasted each day in labs. Some work is more affected by interruptions than others. For example, if you know you have an hour meeting you could start a gel and run it at a low voltage so that it is done when you get back. But for other tasks it is essential to maintain focus for long periods of time, such as programming. Even small interruptions, such as lab members asking you for assistance on something, are very disruptive. This is why I would often work late into the night and do my best work on weekends when there were less people around. This image from u/gremlinsplash pretty much sums it up:

Unqualified researchers/lack of training

Every researcher knows at least one other researcher who is completely hopeless. I’ve seen a graduate student spike all of his samples with ladder instead of loading dye. I’ve seen a postdoc following a midiprep protocol with miniprep columns. I’ve seen centrifuges used incorrectly and damaged. I’ve walked into a cold room of a lab and noticed all of their FPLC columns were uncapped. I’ve seen too much. One problem is the selection criteria for graduate school. "Did you graduate from undergrad and take the GRE? Then welcome aboard." Similarly, because of the shortage of postdocs anyone with a PhD can get a postdoc position. However, a lot of problems can also be explained by lack of training. The postdocs in the lab would ideally be highly trained, and each postdoc should have a graduate student working under them that they train. In turn the graduate student should have an undergraduate that they train. However, I’ve only observed this lab structure in 1 out of the 9 labs I’ve worked in. A growing problem is the lack of training in statistics and data science. As more data becomes available, either through in-house experiments or public databases, labs naturally want to utilize it in their projects. However, no one in the lab is equipped to analyze the data. The PI most likely has no statistical or programming training, and this training is still not part of the standard undergraduate or graduate coursework, so the students and postdocs also don’t have this training. I’ve seen labs perform PAR-CLIP or CHIP-SEQ experiments and then not have anyone to analyze the data. I consulted for a lab with “PAR-CLIP” data, and told them something was wrong since most of their reads were 100 nts when they should have been around 20. After talking with the core facility I found out they decided to amplify the sample with random hexamers. That’s right, amplifying small RNA with random hexamers. And even after discovering this the lab still wanted the data “analyzed”. The computational work I could finish in a day might take another lab months, or they might never figure it out. I’ve seen a postdoc submit a job to a computing cluster that used 40,000 CPU hours and did nothing. And he did this after two people warned him about his SLURM script. Labs should stick to what they know. Each lab should specialize in certain techniques and if they want to branch out into a field such as bioinformatics they should hire the appropriate personnel or work closely with a core facility instead of wasting their time.Foreign postdocs

By foreign postdocs I’m referring to postdocs who have very limited English proficiency. Foreign postdocs are extremely common because the job outlook is better for them than it is for American postdocs. For an American postdoc to get a job as a PI they will need very high profile publications. In contrast, a foreign postdoc can get a couple publications in respectable journals and then return to their country and easily get their own lab. In a lab communication is very important so you can imagine that having lab members speak several different languages is a problem. In my experience foreign postdocs are very hard working, but it is very difficult to tell if they are producing anything of use since they are unable to communicate their work. A lot of progress in a lab originates from discussions among lab members and sharing of techniques and reagents, or even performing work for each other. This type of teamwork gets lost with foreign postdocs. Edit 20161028: The truth is difficult to hear and not surprisingly some have found these comments disturbing. If you would prefer to hire someone you can’t communicate with in the name of diversity, then God bless you, you are a saint. Alternatively, preferring to work with someone I can understand does not make me the devil. That I even have to say that is insane, but there are a lot of crazy people out there. If you want to direct your anti-American sentiment towards an actual case of prejudice against foreign researchers maybe you should look up #Creatorgate where PLOS ONE seemingly retracted a paper over a language issue. I was and still am one of the largest critics of how PLOS ONE handled this controversy and you can read about my thoughts here.Lab turnover

Postdocs in a lab can leave abruptly when they get a job, or their visa runs out, etc. And they often leave behind some unfinished projects. Ideally, before they leave they would teach the person in charge of continuing the project what they did. However, this often doesn’t happen and a lab member may spend over a year simply trying to repeat the results. And often they can’t and just completely wasted a year. Whenever I hear about the funding crisis in science I can’t help but shake my head. There are labs that shouldn’t be receiving a single penny in funding and we want to give them more money? Just like there isn’t really a healthcare crisis, there isn’t really a funding crisis. Most healthcare costs are spent on keeping elderly patients alive a few more weeks or months. If everyone agreed to not receive extreme treatments once they reached a certain age the healthcare crisis would be solved. Similarly, the number of labs that should be receiving funding is fewer than the number of grants, but too many labs full of unqualified and untrained researchers are well funded. If a single person in his apartment can produce more than labs with unlimited resources there is clearly a problem.

If you would like to comment on this post it is available at Medium